Figure 12.12 A fault (white dashed line) in intrusive rocks on Quadra Island, B.C. The pink dyke has been offset by the fault and the extent of the offset is shown by the white arrow (approximately 10 cm). Because the far side of the fault has moved to the right, this is a right-lateral fault. If the photo were taken from the other side, the fault would still appear to have a right-lateral offset.

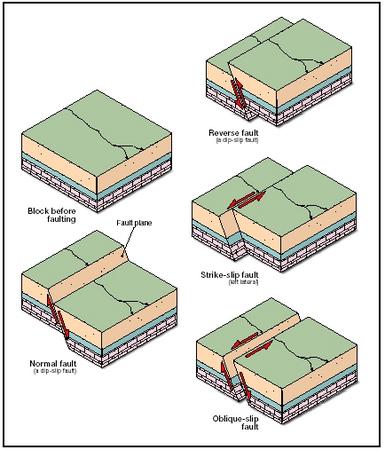

through central Yukon and into Alaska, show evidence of hundreds of kilometres of motion, while others show less than a millimetre. In order to estimate the amount of motion on a fault, we need to find some geological feature that shows up on both sides and has been offset (Figure 12.12). Ī fault is boundary between two bodies of rock along which there has been relative motion (Figure 12.4d). As we discussed in Chapter 11, an earthquake involves the sliding of one body of rock past another. Earthquakes don’t necessarily happen on existing faults, but once an earthquake takes place a fault will exist in the rock at that location. Some large faults, like the San Andreas Fault in California or the Tintina Fault, which extends from northern B.C. Figure 12.11 A depiction of joints developed in a rock that is under stress. įinally joints can also develop when rock is under compression as shown on Figure 12.11, where there is differential stress on the rock, and joint sets develop at angles to the compression directions.

Figure 12.10 A depiction of joints developed in the hinge area of folded rocks. Note that in this situation some rock types are more likely to fracture than others. Ī fracture in a rock is also called a joint. There is no side-to-side movement of the rock on either side of a joint. Most joints form where a body of rock is expanding because of reduced pressure, as shown by the two examples in Figure 12.9, or where the rock itself is contracting but the body of rock remains the same size (the cooling volcanic rock in Figure 12.4a). In all of these cases, the pressure regime is one of tension as opposed to compression. Joints can also develop where rock is being folded because, while folding typically happens during compression, there may be some parts of the fold that are in tension (Figure 12.10). (right), both showing fracturing that has resulted from expansion due to removal of overlying rock. Figure 12.9 Granite in the Coquihalla Creek area, B.C. Fracturingįracturing is common in rocks near the surface, either in volcanic rocks that have shrunk on cooling (Figure 12.4a), or in other rocks that have been exposed by erosion and have expanded (Figure 12.9). A body of rock that is brittle-either because it is cold or because of its composition, or both- is likely to break rather than fold when subjected to stress, and the result is fracturing or faulting.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)